A perfect example of MK-Ultra or Mind-Control or, in other words, externally controlled phonographs and robotic brains.

The Milgram Experiment is a psychological experiment first carried out in New Haven in 1961 and developed by psychologist Stanley Milgram to test the willingness of average people to obey authoritarian instructions even when they are in direct conflict with their conscience. The experiment consisted of a “teacher” – the actual test person – giving a “student” (an actor) an electric shock if they made a mistake. An experimenter (also an actor) gave instructions. The intensity of the electric shock should be increased after each error. This arrangement was carried out in different variations.

Milgram was inspired by the American psychiatrist Jerome D. Frank, who had already investigated the question of what the obedience of arbitrarily selected people depends on as early as 1944. At that time, Frank asked his test subjects to eat twelve tasteless cookies – cf. the soda cracker experiment. The group was told that eating saltless cookies was scientifically necessary. Surprisingly, only ten percent of the participants refused to eat the cookies.

The Milgram experiment was originally intended to explain crimes from the time of national SOCIALISM in a socio-psychological way. To this end, the “Germans are different” thesis should be examined, which assumed that the Germans have a particularly authoritative character. After the first results of the investigation in New Haven, however, this no longer seemed necessary, also because the structure of the investigation was much more fundamental. Milgram received the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s annual award in the social psychology category for this work in 1964. The American Psychological Association, on the other hand, banned Milgram for the experiment for a year after a critic in the American Psychologist magazine accused him of conducting a “traumatizing” experiment that was “potentially harmful” to the subjects. Mainly because of this criticism, which was also expressed by numerous other experts, Harvard University Milgram later refused employment. Milgram himself then noted:

It is “ethically questionable […] to lure people into the laboratory and put them in a position that is stressful.”

The results of the Milgram experiment were first published in an article entitled Behavioral study of obedience, which appeared in the prestigious Journal of abnormal and social psychology. In 1974 Milgram published his work: Obedience to Authority. An Experimental View, in which he put the results in a broader context. The German edition came out in the same year.

Milgram refers, among other things, to the work of the political theorist Hannah Arendt Eichmann in Jerusalem, published in New York in 1963. A report on the banality of evil. This concept of the banality of evil, he argues, comes very close to the truth. The most fundamental finding of the investigation is that ordinary people who only fulfill their task and do not feel any personal enmity can be induced to act in an annihilation process.

The American historian Alfred W. McCoy suspects that Milgram carried out the experiment as part of the CIA-MKULTRA program for research on mind control. This is not only indicated by the timing, but also “the topic, the military connections, the controversial funding by the NSF and their rejection of all later Milgram projects”. These allegations are extensively discussed and denied on the website of Milgram’s biographer Thomas Blass.

Course of the original experiment

Milgram experiment

The entire course of the experiment is staged like a play in which everyone except the test person is initiated. Milgram adopted such an experimental arrangement from his teacher Solomon Asch. A test subject and a confidante of the test director who pretended to be a test subject were supposed to take part in an alleged experiment to investigate the relationship between punishment and learning success. An official experimenter (experimenter, V) determined the actor to be the “student” and the actual test subject to be the “teacher” (L). The administration of an electric shock, with a voltage of 45 volts, should make the subject aware of the physical consequences of electric shock. In addition, the test inventory, reminiscent of an electric chair, was shown on which the “student” was to be tested. This test arrangement with the desired association was never questioned by the test persons.

The experiment consisted of the “teacher” giving the “pupil” an electric shock whenever there was an error in the composition of word pairs. The voltage was increased by 15 volts after each error. In reality, the actor did not experience electric shocks, but reacted according to a predetermined scheme, depending on the voltage set. If the voltage reached 150 volts, for example, the actor asked to be untied from his chair because he could no longer stand the pain. On the other hand, the sitting experimenter demanded that the experiment should be continued for the benefit of science. If the test subject expressed doubts or even wanted to leave, the experimenter asked to continue in four standardized sentences. The sentences were spoken one after the other, after each expressed doubt by the test subject, and after the fourth time led to the experimenter breaking off the experiment. So that the sentences were always the same, they were rehearsed beforehand with the actor, especially to avoid a threatening undertone.

- Sentence 1: “Please, continue!” Or: “Please continue!”

- Sentence 2: “The experiment requires you to continue!”

- Sentence 3: “You absolutely have to continue!”

- Sentence 4: “You have no choice, you have to go on!”

There were other standard sentences in anticipated course situations: If the test subject asked whether the “student” could sustain permanent physical damage, the experimenter said: “Even if the shocks may be painful, the tissue will not suffer permanent damage, so please carry on! ” When the “teacher” said that the “student” did not want to continue, the standard reply was: “Whether the student likes it or not, you must continue until he has learned all the word pairs correctly. So please carry on! ” When asked about responsibility, the experimenter said he took responsibility for whatever happens. The test person responded to the electric shocks with expressions of pain recorded on tape. Milgram had initially lacked these in the pre-test versions of the experiment, but the willingness to obey was then so high that he added them.

The “student” in this case was an inconspicuous American of Irish descent and represented a type of person with whom happiness and serenity were associated. With this selection, an influencing of the behavior by a mental disposition of the test person should be avoided. In addition, it was important that the test subjects could not be inadvertently influenced either by the experimenter or by the “student”. The “teacher” could decide for himself when he wanted to stop the experiment. The experimenter behaved matter-of-factly, his clothes were kept in an inconspicuous shade of gray. His demeanor was determined but friendly.

The test subjects were searched for via an advertisement in the local newspaper in New Haven (Connecticut), whereby the stated fee of four US dollars plus 50 cents travel expenses was promised for the mere appearance. The experiment usually took place in a Yale University laboratory and was marked on the ad as being directed by Prof. Stanley Milgram.

Results

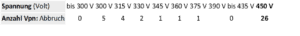

The following table shows the number of test persons (subjects) (n = 40) who stopped the experiment, depending on the strength of the last applied “shocks”.

interpretation

In this case, 26 people went up to the maximum voltage of 450 volts and only 14 broke off beforehand.

Variations of the experiment

The result of the first experiment was so surprising that Milgram carried out over twenty variants with different parameters in each case. Other researchers also made variations.

Proximity between “teacher” and “student”

One variation concerned the proximity between “teacher” and “student”. The following four experimental conditions were set:

- the test subject could neither see nor hear the “pupil”, they only perceived a knock on the wall when the 300 volt limit was reached (“distant room”),

- the “teacher” heard the reactions of the “student” over a loudspeaker (“acoustic feedback”),

- “Teacher” and “student” were in a closed room (“near the room”) and

- the test person had direct contact with the actor (“proximity”).

In the last experimental set-up, the subject, protected by a glove, had to press the “student” ‘s hand onto a metal plate that was supposedly electrically charged.

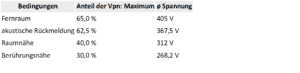

The following table shows the relationship between some varying test conditions, the proportion of test persons (subjects) who delivered the maximum shock, and the corresponding average shock strength.

In the first test series, 65 percent of the test persons were willing to “punish” the “student” with an electric shock with a maximum of 450 volts, but many felt a strong conflict of conscience. No “teacher” stopped the experiment before the 300-volt limit was reached. In the fourth experimental set-up, in which the test subjects had direct contact with the “student”, the voltage level reached was the lowest.

Experimenter’s authority

In a number of versions of the experiment, the experimenter’s authority was varied.

If the experimenter complied with the student’s request to abort and asked the test subject to abort the experiment, the latter followed the instruction without exception.

In a variant of the experiment, in which two experimenters led the experiment and pretended to disagree about the continuation of the experiment, the experiment was stopped in all cases by the test subject.

In a number of variations it has been shown that when the appeals conflict, it is not the contradiction per se and not the general status, but the situation-specific authority that is decisive:

If two experimenter were used, one of whom assumed the actual role of the experimenter, while the other experimenter played the “student” and asked to cancel, 65 percent of the participants went to the maximum. If a “second teacher” instead of the experimenter urged the experiment to be continued while the experimenter remained neutral, relatively few (25 percent) of the test subjects applied the maximum shock.

In a variation by Jerry Burger from 2009, only a few test subjects could be persuaded to stop the experiment by a third person without authority, who urged the experiment to be stopped from the first screams (75 V), as long as the investigator insisted on continuing.

The result of an expansion of the experiment in 1965, however, was that the attitude of other “teachers” has an influence. The proportion of subjects who obeyed unconditionally decreased sharply (to 10 percent) as soon as two other supposed “teachers” who opposed the experimenter took part in the experiment. If the two “teachers” were in favor of continuing the experiment, 90 percent of the test subjects followed.

In a further variation, the experimenter did not pose as a researcher at the renowned Yale University, but as a scientist at the fictitious commercial Research Institute of Bridgeport, whose rooms were in a shabby office building in a business district in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The number of test subjects who used the highest voltage fell from 65 percent to 48 percent. However, this difference is not statistically significant.

Part of another variation was that Milgram left the room and an actor, who presented himself as a test subject, led the experiment. Here, the proportion of subjects who went up to the maximum level fell to 20 percent.

Presence of the investigator

In addition, the presence of the test leader was varied, who could either be directly in the room, only reachable by telephone, or absent. In the latter case, the instructions were given using a tape recorder.

The absence of the experimenter caused the obedience rate to be three times lower than in the experimental setup with his presence.

Differentiation by gender

In a test set-up in which women were given the electric shocks, there was no significant difference in the drop-out rate compared to tests with male test subjects: In 2006, Jerry Burger’s experiment at Santa Clara University was repeated under modified conditions. Women were involved, the maximum voltage was 150 volts. 70% of the subjects, none of whom knew about Milgram’s experiment, went up to maximum strength. The difference compared to Milgram’s original experiment (83% of the subjects went to 150 V) is not statistically significant.

Reaction of the test subjects

All test subjects in the original experiment showed a troubled state of mind, had conflicts of conscience and were excited. Milgram particularly noticed a nervous laugh that 35 percent of the test subjects uttered. One observer described the emotional state of a “teacher” as follows:

“I observed a mature and initially self-confident businessman who entered the laboratory smiling and full of self-confidence. In twenty minutes it was a twitching, stuttering wreck that was rapidly approaching a nervous breakdown. He kept tugging on his earlobe and wringing his hands. At one point he hit his forehead with his fist and mumbled, ‘Oh god let’s stop’. Yet he continued to respond to every word the experimenter said and obeyed to the end. “

It was found that people who rated personal responsibility for their behavior high were more likely to break off the experiment and contradict the investigator.

Long-term consequences for the test subjects

In order to do justice to the ethical aspects, the test subjects received detailed information about the experiment and its results after the test series was completed. In order to identify possible long-term damage, the test persons were visited and questioned again in a random sample one year after the experiment. According to Milgram, the experiment did not show any harmful effects on the subjects’ psyche. 83 percent of the participants stated that in retrospect they were happy to have taken part in the experiment. Only one subject in a hundred regretted his participation. Most participants stated that they had learned something about themselves and that they therefore wanted to be more suspicious of persons in authority in the future. In contrast, other long-term studies report nervous breakdowns and post-traumatic stress disorder, and some participants said forty years later when they were examined again that they had never got rid of this shock, that trauma, that is, a trauma of having been the perpetrator. The Freiburg psychologist Joachim Bauer concludes “that this experiment made the persons concerned, against their own intuition, against their natural human instincts […], to follow the authority here”.

Consequences and Consequences for Psychology

Today, a comparable experiment would be rejected by many psychologists as unethical because it subjects the subjects to strong internal pressure and is misled about the real purpose of the experiment. In response to this attempt, many universities established ethical guidelines on the admission of psychological experiments. It is not known whether the knowledge gained was used by the military and secret services.

Milgram commented on the results of his experiment as follows:

“The legal and philosophical aspects of obedience are enormously important, but they say very little about how most people behave in specific situations. I did a simple experiment at Yale University to find out how much pain an ordinary person would cause another simply because a scientist asked him to. Rigid authority opposed the participants ‘strongest moral principles not to harm other people, and although the subjects’ screams of pain rang in the ears of the test subjects, in the majority of cases authority won. The extreme willingness of adults to follow an authority almost indefinitely is the main finding of the study, and a fact that needs urgent explanation. “

To this day, obedience to authority is theoretically considered insufficiently clarified. Although Milgram suspected a personality basis for obedience to authority and denial, he could not substantiate it. Instead, he assumed two functional states:

- a state of autonomy in which the individual feels responsible for his or her actions, and

- an “agent state” into which it is placed by entering an authority system and no longer acts on the basis of its own objectives, but becomes an instrument for the wishes of others.

The experiment showed that the situation led most of the subjects to follow the experimenter’s instructions and not the victims’ pain. Prompting was most effective when the experimenter was present and most ineffective when instructions were given by tape or telephone. The closeness to the “student” also influenced the willingness to break off the experiment. Virtually all test subjects went up to the highest shock level without any feedback from the “pupils”, while only 30 percent reached the highest level with direct contact.

This Milgram project is just a shadow compared to the real MK Ultra projects. But you can read that in the book: The Power of Manipulation – from rhetoric to MK-Ultra.